Last week I wrote about the importance of the middle years (ages 9-14). We give a lot of attention to infancy and to the teen years because of the perceived importance. But it’s hard to overemphasize how important it is to navigate the middle years with intentionality given the weight of young people’s internal decisions during this season of life. But it’s not necessarily obvious what intentionality looks like in the middle years.

How to Navigate the Middle Years with Intentionality

The reality of the middle years took me a little bit by surprise with my oldest 2 daughters. They are 17 months apart so they hit this season of life pretty close together. In some ways, it started with more responsibility. They had more homework requirements at school and were also more helpful in cleaning up after dinner, so they stayed up to do those things while one of us put the boys to bed. That meant they were up at the time of night that I might stream a 20-minute show. So they watched it with me. And to my great surprise, they got the jokes!

Around this same time, the girls engaged in more specific activities like choir and middle-school clubs. They were also less interested in watching their brothers’ elementary sports practices, so they started running the track upstairs with me rather than playing off to the side of the gym. The drives to their extracurricular activities and the waiting periods often resulted in one-to-one time.

It was in the driving back and forth or in the time spent walking the track that conversations came up. You don’t have to do book studies with your child on the changes that happen in middle school to have meaningful interactions. If you are aware and present, opportunities are all around–even in the midst of very busy schedules.

The Context of the Parent-Child Relationship in Middle School

The social changes that came with these middle years took me by surprise. We had four kids in five years. Like many parents, I found the infant and preschool years both mentally challenging and physically exhausting. I appreciated the relief of the elementary years. Though their reliance on me was less “around-the-clock”, my daily routine was still built around their needs. Our work schedules were determined by their school start and end times. After we cleaned up dinner, we started preparing for the next day by packing lunches and setting out clothes. These perfunctory duties were reminders that our kids required our support for their survival. But then they got taller. They started sleeping in. When they did wake up, they could make their own breakfast and turn their homework in without parental involvement or oversight. They even started borrowing my clothes.

These important and concrete changes cause parents to begin to release more and more responsibility to their children. Overall, this is healthy and necessary. But given the sensitive nature of this period in a child’s life, it’s important to navigate the social context with great intentionality.

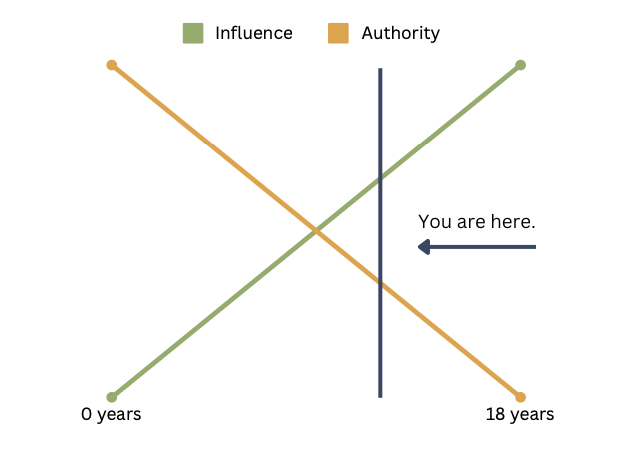

I previously wrote about the line graph that shaped my parenting. I updated the line graph here to give you a sense of where you are as a parent of a middle schooler. You’ve crossed the halfway point where influence and authority intersect. This doesn’t mean you don’t place healthy boundaries around your child. Boundaries in this season are crucial. But it does mean that this is a time to engage your child in more complex ways than just building positive routines and holding boundaries.

Lessons I’ve Learned from Master Parents

I’ve had the opportunity to watch some incredible parents navigate this season of life with their children successfully. The ones who raise resilient children with a strong sense of identity have a few things in common. I’m going to call them “Master Parents” in part to be funny. But mostly because they could teach a Master Class on parenting.

They offer their child a strong narrative of identity

“Master” parents don’t outsource their values to their school or just leave it open to popular culture or whatever seems to secure their child’s attention. Something will be built whether we provide our children a strong narrative. Be the dominant voice in their life. Don’t let others define them in this most important season of their life. Challenge them. Talk to them. Make conversations about important things the norm.

A lot of people attempt to do this by separating or protecting their children from any influence that runs counter to their values. Certainly, we should have standards in our homes and should protect our children from unwholesome content and people. But we should be as vigilant about building their internal resilience as we are about monitoring their external content.

When our kids were younger, my husband Clay talked about the power of being distinct. He made it cool to stand up for what’s right and hold a standard. He didn’t do this in structured family meetings at night, but he used dinner table conversations as a starting point for more meaningful conversations. We didn’t buy tickets to the trending concerts or movies. In fact, we hardly watched TV at all during the week. We connected our kids to a like-minded community in our church. Our activities and conversations centered around those values rather than passing interests and hobbies. We built a life that looked like the values we wanted to reflect and integrated our kids into it.

They separate their own identity from their child’s performance

“Master” parents aren’t trying to clone themselves and don’t perceive their children’s successes or failures as their own. They have a separate identity and perceive themselves as facilitators in the development of their child’s own identity. This allows parents to distance themselves from the emotional highs and lows of parenting middle schoolers. It also ensures that their children have space to develop into the unique identity they’ve been given.

Several years ago, one of the teachers at our school had requested to meet with her student’s parents alone so she could honestly bring up some concerns to the parents. When I asked her how the meeting went, she said it unfortunately felt like the mother’s personal parent-teacher conference. Her identity was so wrapped up in her child’s performance that when she described her concerns, the mother took it personally as if she was saying these things about her. The father’s response was better. He shared that he recognized the same traits and asked questions about how to respond and how to provide support. He recognized the child as a separate, immature individual who needed his support. That empowered him to father his child through these challenges.

We are not our kids. And they are not at their best, most mature state. By definition of their state of development, they are immature. That’s not a negative statement about them, it’s a reasonable expectation for us. Their failures are usually developmentally normal. They are opportunities to learn, not reflections of poor parenting. So provide the appropriate pressure, adjustment, and discipline. But don’t do it out of a sense of embarrassment and don’t get defensive. This helps us respond with the appropriate pressure or support that will help keep our children in between the ditches.

They place healthy boundaries around their children

Even though your influence outpaces your authority at this age, middle schoolers still need boundaries. The most important boundaries at this age are usually social boundaries. Master parents remain vigilant about where and how their kids spend their free time.

Your child may begin pairing off into more exclusive relationships at the beginning of their middle years. I’ve talked with parents who are hesitant to influence these relationships. That concern is premature. This is one of the last seasons you have to set boundaries on when and where your child can be. It gets harder from here. It’s okay to have honest conversations with your child about their friendships and to limit the time they spend with peers who cause concern.

Social influences don’t only refer to in-person experiences but also refer to how middle schoolers engage in the virtual world, what activities they pursue, and the nature of family life in your home. It’s important to vigilantly monitor what your kids are doing online as Jonathan Haidt’s book The Anxious Generation so clearly lays out.

They create opportunities to influence

Master parents don’t just create rules limiting what their children can do or where they can go. They build a joyful experience within the boundaries. If you make a rule that your kids should spend most of their evenings at your house, be sure that that time isn’t just spent watching movies or surfing the internet. Build a rich family life. Engage them in a positive community. Utilize every tool available to help your child build a values-based lens. Use movies and music as opportunities to facilitate discussion. Don’t just watch something controversial and assume the opinions they are forming are healthy.

Don’t take this as an imperative to become your child’s full-time entertainment facilitator. A well-intentioned family I know wanted to build a joyful home life. Every time we turned around they had a new toy or machine or hobby. They bought a boat because they envisioned weekends on the lake with the family. When their child expressed interest in basketball, they put up a goal and bought a membership to a gym where they could play. They enrolled their kids in lessons for each hobby they pursued. They took elaborate vacations. By the time their kids entered high school, the parents were exhausted from their full-time commitment to entertain their kids in the evenings and in the summers. And the kids didn’t come across as particularly grateful or engaged in any single activity.

The parents who seem to navigate these years with balance are the ones who create opportunities for influence inside the mundane routines of life. Their lives aren’t extravagant. Many of them lead busy work lives, but they keep their evenings simple so there is space to connect and build their children.

The Middle Years on the Newcomb Farm

Between school and church events, our lives were pretty full when our kids middle schoolers. A handful of our kids played on school sports teams, but we didn’t do a lot of extracurricular activities outside of that. We also didn’t allow video games in our home. Most nights we didn’t stream entertainment and when we did, it was only allowed for one show well after dark–and almost always watched together. Sometimes, we would go to the park and play ball together. Sometimes neighbors or grandparents would swing by for a visit. We routinely invited company over for dinner and had our kids stay in the living room to connect with them while they were there. Most of the time, we just stayed busy working on our projects around the house. The kids were usually invited to join. It wasn’t particularly exciting.

It was in this boredom, that one of our sons committed to self-run basketball drills. In high school, he became a high-performing athlete. One of our sons started using the tools around our house to create things–a hobby that has spurred several side interests. One of our girls engaged deeply in academics and one in crafting and creating. Most of them learn to shoot bows with Clay. They also had their own fun together. Some of these activities paid off in the form of career interests or scholarships. Some didn’t.

We certainly weren’t perfect parents, but our values shaped our priorities and our home life. The simplicity of that created a household context that offered space for our values and relationships, allowed our kids to learn about themselves and finely tune some interests, and took the pressure off us as parents. We put boundaries around what they could do and where it could be done (at this age it was mostly at home, church, and school). After dinner and chores wrapped up, if there was still time in the day, everyone had space unoccupied by entertainment, distraction, and pop culture to do their own thing. That space and that togetherness presented a lot of opportunities for meaningful conversations. Those conversations and experiences crafted a strong identity and internal compass that was a comfort to us when we handed each of them car keys a few years later. And it gave us the tools we needed to have some bigger conversations when our kids hit high school.